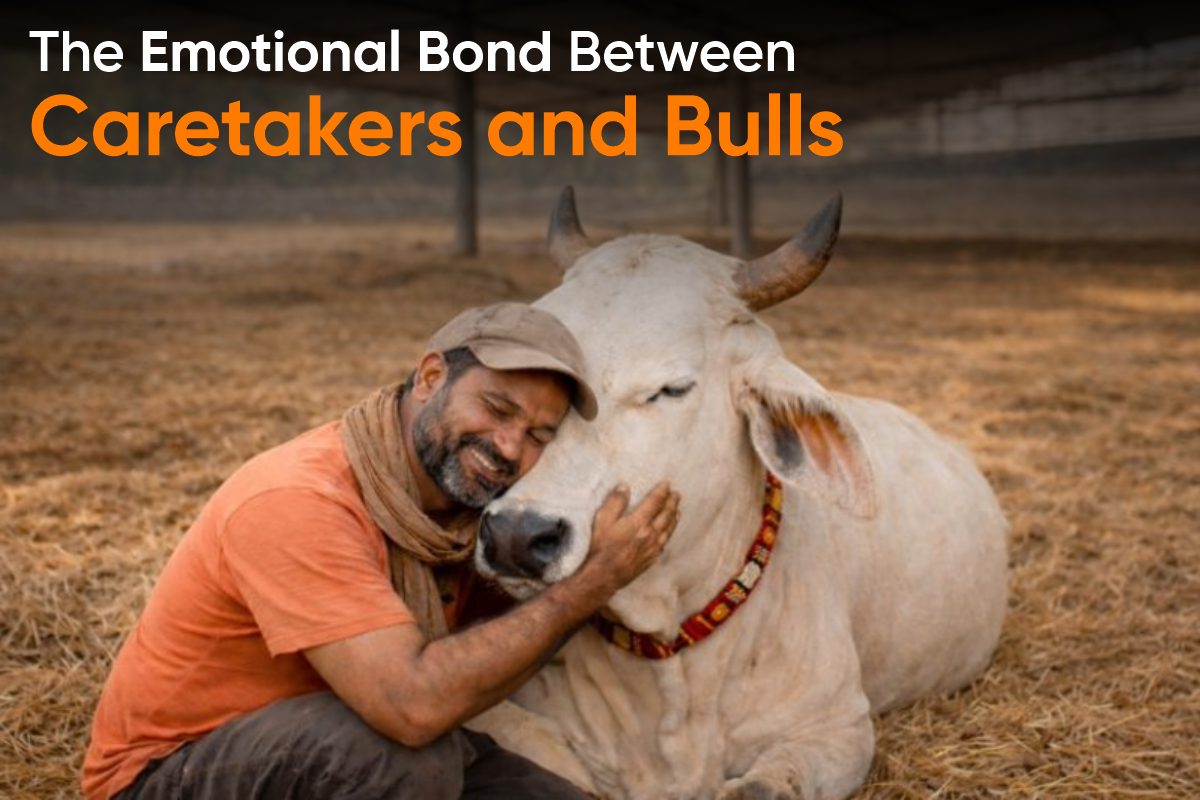

When we speak about attachment, we often imagine a child holding a parent’s hand, a son caring for his mother and a person crying over the pain their loved one is suffering. But we would rarely imagine a caretaker standing quietly beside a rescued bull in a rural shelter. Yet, if John Bowlby were to walk through a gaushala in India today, he might recognize something deeply familiar. The same patterns of trust, proximity, and emotional regulation that shape human relationships quietly unfold between humans and animals every single day.

Across the nation, in spaces dedicated to cow shelter care in India, bulls are often the overlooked residents. They are no longer needed for farming, no longer useful for breeding, and often abandoned once their economic value declines. When they arrive at shelters, they do not just carry physical exhaustion. Many carry signs of chronic stress, heightened alertness, avoidance of touch, flinching at sudden movement. Well, here we realise that trauma is not a human monopoly.

This is where bull shelter caretakers enter the story

Attachment theory suggests that living beings are biologically wired to seek safety through connection. Bowlby described a “secure base” i.e. a figure who provides safety, allows exploration and provides emotional stability; and in bull shelters, caretakers unknowingly become that secure base. It is seen simply in how they show up every day, feed at fixed hours, clean wounds without impatience, speak in low and steady tones and then return back.

Consistency is the beginning of attachment

In the early days, many bulls keep their distance. Just as Bowlby described children in the protest or despair stage of separation, animals who have experienced abandonment often oscillate between aggression and withdrawal. Some refuse food, some charge defensively, or some freeze completely. To an outsider, this may look like stubbornness but to someone who understands the emotional bond animals form with caregivers, it looks like fear of trusting again.

Over time, something changes

A bull who once stood at the far edge of the enclosure begins to stand closer during feeding. One who avoided eye contact begins to linger when the caretaker finishes cleaning the trough. These are not dramatic cinematic moments captured in a Bollywood Hindi movie; they are micro-signals of safety being restored.

Bowlby spoke of “proximity seeking”, that is the instinct to move closer to a figure when feeling uncertain very solidly. In shelters practicing genuine animal care compassion, this is visible in small behaviors. A bull nudges a caretaker’s shoulder, another follows familiar footsteps across the yard; all these are attachment behaviors. They are not trained tricks but biological responses to consistent care.

What makes this bond unique is that it exists without verbal reassurance. There are no promises spoken, or explanations given. Trust forms through repetition and predictability. Neuroscience supports this. Mammalian brains regulate stress through co-regulation. Calm presence lowers cortisol and predictable interaction stabilizes the nervous system. This applies to humans and animals alike.

In many cases, bull shelter caretakers report that certain bulls respond differently to specific individuals. Some prefer one caretaker over another. This mirrors Bowlby’s idea of selective attachment. Even in environments where multiple people provide care, a primary bond can emerge. It is not about favoritism; it is about emotional resonance.

The bond also reshapes the caretaker

Attachment theory is reciprocal. While much focus is placed on how dependents attach to caregivers, caregivers also internalize the relationship. In the long-term, many caretakers working in cow shelter care in India describe a sense of responsibility that goes beyond duty. They notice subtle changes in appetite. They recognize the sound of distress calls and identify shifts in mood, signalling the development of emotional attunement.

This is where the concept of “internal working model” becomes powerful. Bowlby explained that early bonds shape how individuals perceive safety and trust in future relationships. When caretakers form stable bonds with animals, they often report increased empathy and emotional awareness in other areas of life. The act of sustained animal care compassion strengthens their own capacity for secure attachment.

It is psychological

The life cycle of bulls in cow shelter care in India also reflect another dimension of attachment theory: loss. Some bulls arrive after years of labour. Some are rescued from neglect and many even come after being displaced. Hence, the separation trauma is quite visible. When a bull loses a long-time enclosure companion, behavioral changes that take place within them mirror human grief patterns like withdrawal, reduced appetite, and decreased activity. Caretakers often adjust routines, increase physical presence, or rearrange housing to reduce distress.

The relationship is co-regulation

There is a misconception that attachment weakens resilience. In reality, secure attachment enhances it. Bulls that develop stable bonds with caretakers often show improved feeding patterns, reduced aggression, and healthier recovery from illness. The secure base allows them to rest and rest is biological safety.

In shelters across India, the daily rhythm continues quietly. Buckets of water, fresh fodder, gentle brushing, medical checkups, and many more. Obviously, none of this makes headlines yet within these repetitive actions, attachment cycles form and strengthen. The emotional bond animals develop with humans in these environments is not dependency, it is adaptive trust. It allows an abandoned being to experience predictability again and it also allows a human to practice patience without expectation of verbal gratitude.

This bond also challenges a societal narrative. Bulls are often culturally symbolic but practically neglected. The people engaged in bull shelter caretakers roles do not romanticize the animals, they understand their size, their strength, their unpredictability and show that compassion here is grounded in reality.

When viewed through attachment theory, these shelters become relational ecosystems that provide a secure base and a safe haven allowing opportunities to seek proximity, process grief and even co-regulate. It’s the same psychological architecture that shapes human development that quietly operates in these spaces. Perhaps what makes this bond powerful is its simplicity. It does not rely on language but on presence.In a world that measures value in productivity, shelters practicing genuine cow shelter care in India remind us that worth can exist beyond economic utility. In this quiet exchange we witnessed at Sadbhavan Vruddhashram, between a caretaker and a bull, we see attachment not as theory but as an experience lived. It is not dramatic nor exaggerated; it’s just steady, daily, human connection extended across species. And sometimes, that is enough for the ones who don’t speak the language we do, but their eyes convey enough.

Categories

Latest Posts

Tags

Contacts

Rajkot – 360110